«Золотий» вік Соломона

Міцний початок

До останніх Давидових днів його син Соломон перебуває в тіні. Він зовсім не проявляє своїх амбіцій. За нього переживають інші — мати Вірсавія, пророк Натан, священик Садок, воєначальник Беная. Вони нагадують царю його клятву передати трон Соломонові. Лише тоді Давид діє: за його наказом Соломона посадили на царського мула й у Ґіхоні помазали на царя над Ізраїлем (1Цар.1:33-34, 38-39).

Соломон не шукає царства, царство знаходить його.

Але як тільки ріг єлею виливається на його голову, Соломон відразу ж змінюється. З цієї миті ми бачимо іншого Соломона. Він діє швидко й рішуче, але разом із тим розважливо.

Перетворення непомітного персонажа в головного героя саме по собі дивне. Це показує, що Соломон був мудрий завжди — навіть до своєї знаменитої молитви-прохання про мудрість.

Він чекав потрібного часу й жодним чином не квапив подій, але все помічав і оцінював.

Він запам’ятав і виконав кожне слово свого батька. Він не поспішав із висновками, але й не зволікав із виконанням уже прийнятих рішень.

На початку свого царювання він милує Адонію, попереджаючи: «Якщо знайдеться в ньому зло, то помре» (див.1:52).

Він не хоче нічиєї смерті, але й не бажає залишити зло безкарним. Цього він навчився в батька — милосердю, терпінню, справедливості.

А після смерті Давида Соломон готовий розплатитися з тими, кого батько милував до певного часу — з підступним Йоавом і лихословом Шім’ї.

Соломон дає всім ще один шанс, але лише один, останній. Адонія плете інтриги й за це вмирає. Йоав бере участь у цих же інтригах — і покарання знаходить його навіть у скинії. Шім’ї порушує «підписку про невиїзд» — і покараний мечем.

Завдяки своїй рішучості Соломон зробив царство «дуже міцним» (див.2:12). Він швидко розплачується за рахунками батька й розгортає нову сторінку.

Мудрий вибір

Незважаючи на те, що царювання Соломона було «дуже міцним» і народ йому «дуже радів», незважаючи на вигідний династичний шлюб з фараоном і внутрішньополітичну стабільність, цар пам’ятав про батьків основний заповіт — «стерегти накази Господа, Бога свого, щоб ходити Його дорогами…» (1Цар.2:3).

Соломон і сам «полюбив Господа» (1Цар.3:3). Він не тільки беріг вірність батькові, ходячи «постановами Давида». Він хотів знати Бога, у Якого батько вірив, заповіт із Яким обіцяв царство Давидовим нащадкам навіки.

Соломон і сам «полюбив Господа» (1Цар.3:3). Він не тільки беріг вірність батькові, ходячи «постановами Давида». Він хотів знати Бога, у Якого батько вірив, заповіт із Яким обіцяв царство Давидовим нащадкам навіки.

Цікаво, що основна зустріч Соломона з Богом відбулася вві сні. Але розмова була цілком предметна й пам’ятна. Бог готовий виконати прохання. Але хіба це не випробування? Хіба просити Бога про щось не означає висловити своє сокровенне, назвати себе та Його правильними словами, поставити себе в певне становище перед Ним, зайняти потрібне місце? Соломон гідно проходить випробування.

Він не згадує про свої успіхи, а зізнається, що не знає, як керувати народом, і просить Божої допомоги в цьому.

Він не згадує про свої успіхи, а зізнається, що не знає, як керувати народом, і просить Божої допомоги в цьому.

Зазвичай царі думають, що управляти вміють, — бо ж не були б царями. Вони мріють про інше — про довге життя, перемоги й багатство. Богові було угодно, що Соломон не просив про це, а просив розуму, визнаючи тим самим свою нерозумність без Бога, визнаючи Бога справжнім Царем.

Соломонів мудрий початок неодмінно принесе успіх. Соломон стане знаменитим на всі віки як могутній і багатий, непереможний і славний. Але насамперед — як мудрий.

Мудрість Соломона починалася зі звернення до Бога як до Царя. Буде мудрий кожен, хто називає себе рабом Бога, хто каже: «Ти поставив Свого раба», і «без Тебе не знаю як».

…Іноді лідери народжуються вві сні.

Як пісок морський

Царство Соломона було не тільки твердим і мудрим. Воно було мирним і щасливим. Син Вірсавії шанував батька, але пам’ятав про хіттеянина Урію. Якщо народження Соломона було пов’язано з війною й нещастям, несправедливістю й зрадою, то життя Соломона повинно було спокутувати це минуле — заради батька й матері, заради кращого майбутнього для всього народу, втомленого від палацових інтриг і нескінченних воєн.

«Був у нього мир зо всіх сторін його навколо. І безпечно сидів Юда та Ізраїль, кожен під своїм виноградником» (1Цар.4:24-25).

У стайнях відпочивали сорок тисяч коней для колісниць і ще дванадцять для кінноти. І все-таки царство розширювалося не війною. Секрет був у іншому: «Дав Соломону Бог мудрість та розуму, а широкість серця як пісок на березі моря. І збільшилася Соломонова мудрість над мудрість усіх синів сходу та над усю мудрість Єгипту» (4:29-30). Ось де сила.

Не маючи змоги передати достаток тих днів, хроніст вдається до образного вислову: «як пісок морський». І ці ж слова — про життя народу: «Юда та Ізраїль були численні, як пісок біля моря, їли, пили й веселилися» (4:20).

Один і той самий вираз. При повноті мудрості з’являється достаток і в скарбниці, усе процвітає. Перепадає і простому люду. У будь-якому разі людей не женуть на війну й не забирають у них останнє на потреби оборони.

Кордони розширюються, багатство росте, сусіди поважають, навіть здалеку подивитися й подружитися приходять. При цьому цар не забуває промовляти притчі й складати пісні. У цьому, судячи з усього, він також перевершив батька Давида — тільки пісень придумав «тисячу і п’ять».

Якщо всього так багато, «як морський пісок», то навіщо рахувати? Та в царя враховані кожен кінь, кожна вівця, кожна пісня, кожна людина.

Навіть коли до нього приходять блудниці сперечатися про дитинку, він терпляче розбирає справу, відновлюючи справедливість та повертаючи сина його матері. Справжньою матір’ю буде та, яка готова віддати свого сина іншій, аби зберегти його життя, аби йому було добре. Справжнім царем буде той, хто служить загальному благу. «Я» і «моє» мають бути на останньому місці. Його логіка дивує народ настільки, що «почув увесь Єрусалим про той суд, що цар розсудив, і стали боятися царя, бо бачили, що в ньому Божа мудрість» (3:28).

«Як пісок морський». Так може жити будь-який народ, що боїться Бога, шукає Його мудрості. На жаль, для Ізраїлю це благоденство тривало недовго. Воно було лише тінню того щастя, яке ми досі чекаємо в Божому Царстві. Згадуючи дні Соломона, ми думаємо не про минуле, але про майбутнє, ми кажемо Царству Божому: «Гряди!»

Храм Господу

Як тільки Соломон зміцнив царство, забезпечив мир і «відпочинок навколо» (так що «не стало противника й не стало більше перепон» (1Цар.5:4), «почав він будувати храм Господу» (6:1).

Давид задумав, а Соломон не забув батьківського бажання й виконав задумане. В обох випадках це було пов’язано з особливим почуттям вдячності Богу за даровані спокій і процвітання.

Давид подумав про храм саме тоді, коли «осів у своєму домі, а Господь дав йому відпочинок від усіх ворогів його навколо» (2Сам.7:1). Він вважав, що якщо цар живе «в кедровому домі», то несправедливо, що «Божий ковчег знаходиться під завісою». Бог не заперечував такого дару, хоча нагадав царю, що «не пробував у домі… але ходив у наметі та шатрі»й не просив собі «кедрового дому», але був з Давидом «в усьому» (2Сам.7: 6-7,9).

Цар дуже хотів мати поруч із домом своїм — дім Божий, постійну Божу присутність, символ Божої сили й особистого покровительства.

Але Бог був і буде «в усьому». Він узяв Давида «від овець», зберігав його в небезпеках, зробив могутнім царем. Але також карав його й викривав. Бога не можна закрити в храмі, не можна зробити придворним і зручним.

Бог не відмовляється від наших храмів, приймає наші подарунки, але залишається вільним, суверенним і верховним. Він Цар над царями.

Храм без Бога — лише камені й дерево. Бог живе серед нас тоді, коли ми вірні Йому. Якщо ми не виконуємо Його заповідей та відступаємо від Бога, то ніякі стіни не зможуть утримати Його присутності. Ніхто, навіть цар Соломон, не міг і не зможе управляти Богом.

Храм без Бога — найбільш непотрібна будівля в місті, найбільш марна трата грошей, найстрашніший символ невір’я й невірності.

Але якщо ми віримо й вірні Богові, то Він живе прямо серед нас — і в храмі з каменів, і в наших простих будинках, і в наших розбитих серцях.

Дім Богу і свій дім

Соломон дуже старався догодити Богові. Він віддавав Богу найкраще — як це оцінювалося в стародавньому світі, як він сам розумів.

«І ввесь храм він покрив золотом аж до кінця всього храму, і всього жертівника…» (1Цар.6:22). Храм — це вже не оселя. Тут рясніє золото. У скинії був жертовник із дерева, приналежності до нього — з міді. Тепер усе золоте. Та й дерево інше — не акацієве, а розкішний кедр. І замість Бецаліїла — Хірам із Тира.

Накази про скинію давав Сам Бог самому Мойсеєві. План храму придумав цар. Наймудріший, але лише цар.

Храм він будував старанно — сім років. «А свій дім Соломон будував тринадцять років» (1Цар.7:1). Розміри храму були значно більші, ніж розміри скинії, але розміри царського дому — ще більші.

Той, Хто створив всесвіт, задовольнявся простою скинією. Храм більший, але тісніший. Те, як ми облаштовуємо свій простір, багато говорить про нашу віру. Ось Твій дім, Боже. Ось — мій. Окремо — дочки фараонової. Кожному своє. Але хіба мій дім — не Його? Помістивши Бога в храм, ми забираємо в Нього все інше, ми царюємо поза храмом. Якими б не були чистими й гідними наші наміри, це не Божий задум, це не Божественний порядок.

Бог не житиме в золотій клітці або будь-якому іншому окремому місці. Він хоче жити разом із нами, Він хоче жити в нас.

Храм без храму

Релігія — не тільки про поклоніння Богові, але також про нескінченні спроби присвоїти Бога, використати у своїх людських потребах.

Релігійні місця виділяються для того, щоб визначити й обмежити зони священного.

Цар Соломон при всій своїй мудрості йшов за цією логікою.

Всевишній, вірний Своєму завіту з Давидом, показував свою присутність у хмарі. Хмара — не річ. Її не привласнити й не закрити в храмі. Але Соломон продовжував гнути свою лінію: храм — це житло Бога, місце для Його перебування навіки.

Священики не можуть стояти, явлення слави Господньої ламає порядок служби, але цар стоїть на своєму.

«І не могли священики стояти й служити через ту хмару, бо слава Господня наповнила храм Господній. Тоді Соломон проказав: «Промовив Господь, що Він пробуватиме в мряці. Будуючи, я збудував оцей храм на оселю Тобі, місце, Твого пробування навіки» (1Цар.8:11-13).

Соломон знав історію, пам’ятав про часи Мойсея, коли слава Божа наповняла скинію, але при цьому орієнтувався на моделі сусідів, поглядав на Єгипет і Тир. У Мойсей було інакше. Храм не стояв на місці. У Бога не було місця, у Бога був шлях, і Бог вів скинію й народ за Собою. «А хмара закрила скинію заповіту, і слава Господня наповнила скинію. І не міг Мойсей увійти до скинії заповіту, бо хмара спочивала над нею, а слава Господня наповнила скинію. А коли підіймалася хмара з-над скинії, тоді рушали сини Ізраїлеві в усі свої подорожі. А якщо хмара не підіймалася, то не рушали вони…» (2М.40:34-37).

Об’явлення Івана Богослова відкриває дивовижне майбутнє, у якому храму не буде. «А храму не бачив я в ньому, бо Господь, Бог Вседержитель — то йому храм і Агнець» (Об.21:22).

У цьому ж світі ми ще шукаємо ті рідкісні місця, де можна переживати славу Божу. Але слова Христа звучать все голосніше — як пророцтво і виклик: «…Надходить година, коли ні на горі цій, ані в Єрусалимі вклонятися Отцеві не будете ви… Бог є Дух» (Ів.4:21,24).

Місце зустрічі

Соломон хоче відчувати Бога поруч, поблизу. Він хоче бути впевненим і спокійним. Тому храм Богу й царський палац будують поряд. При всій мудрості Соломона ми не бачимо в ньому того багатого внутрішнього життя, яким відзначався Давид. Соломон не співає пісень, він промовляє притчі. Він багато знає і розуміє, але не так багато почуває.

Соломон не вміє молитися, як його батько, у пустелях і печерах. Йому потрібен храм — особливе місце, через яке можна підтримувати зв’язок з Богом.

Він розуміє, що справжнє місце Бога — «на небесах», але просить Його «бути на зв’язку», відвідувати храм, чути й бачити, хто молиться в ньому.

У день відкриття храму Соломон молиться вкрай відверто: «Бо чи ж справді Бог сидить на землі? Ось небо та небо небес не обіймають Тебе, — що ж тоді храм той, що я збудував? Та Ти зглянешся на молитву Свого раба … щоб очі Твої були відкриті на цей храм уночі та вдень… І ти будеш прислухатися до благання Свого раба, та Свого народу, Ізраїля, що будуть молитися на цьому місці. А Ти почуєш на місці Свого пробування, на небесах, — і почуєш, і простиш» (1Цар.8:27-30).

Цар просить Бога зглянутися над нашою людською слабкістю. Нам потрібні особливі місця для зустрічі з Богом. Ми втратили здатність спілкуватися з Ним постійно, відчувати Його живу присутність кожну хвилину й на кожному місті.

Храм створює атмосферу для такої зустрічі, уводить нас у спілкування. Так було для Соломона та його багатьох наступних поколінь.

Із роками храм як місце зустрічі з Богом перетворювався на пам’ятник про минуле, про великих царів і їхні зустрічі з Богом.

Те ж саме відбулося і з християнською церквою. У кращому разі тут зустрічаються люди. Але зустрічі з Богом трапляються щораз рідше.

Де наше місце зустрічі? Чи можемо ми так шукати Бога, щоб зустрічати Його й у храмі, і в печері, і на роботі, і вдома, і на війні, і в благополуччі?

Безумна старість Соломона

У Соломона був мудрий початок. Але останні дні були наповнені божевіллям. Можливо, його голова працювала так само добре, як і раніше. Але ось серце, серце його повернулося до інших богів, богів численних чужоземних дружин і наложниць. «…На час Соломонової старости, жінки його прихилили його серце до інших богів, і серце його не було все з Господом» (1Цар.11:4).

Біда прийшла зсередини, відступництво дозріло в серці. І мудрість не спасла.

Той самий Соломон, який побудував храм Господу, «пішов за Астартою… за Мілкомом… збудував жертівника для Кемоша… та для Молоха…»

Цікаво, що хроніст порівнює Соломона з Давидом і зазначає: «серце його не було все з Господом, Богом, як серце його батька Давида» (11:4),«не йшов певно за Господом, як його батько Давид» (11:6).

Чи не здається нам це порівняння дивним? Адже Давид грішив не менше, убивав наліво й направо, забирав чужих дружин. Але справа не в цьому. Його серце, як виявляється, було з Господом і йшло за Ним. Тому він співав псалми, а не писав притчі. Тому він каявся, а не вчив інших.

Відомий реформатський богослов Джеймс Смірт у своїй останній книзі «Ти — те, що ти любиш» («You are what you love»), заперечує думку Декарта, згідно з якою «Я» зводиться до ідеї, ніби людина — банк або банка ідей. Навпаки, «бути людиною означає бажати царства — якогось царства… Мої бажання визначають мене».

Це означає, що основні процеси розгортаються не в голові, а в серці.

Серце Соломона збочило. Він хотів і шукав царства, у якому буде ще більше золота й ще більше дружин. Він дозволив своїм бажанням відвести себе далеко від Бога, до неправдивих богів і храмів.

До чого схиляється наше серце? Як ми уявляємо бажане «царство»? Що ми любимо насправді?

Кінець «золотого століття»

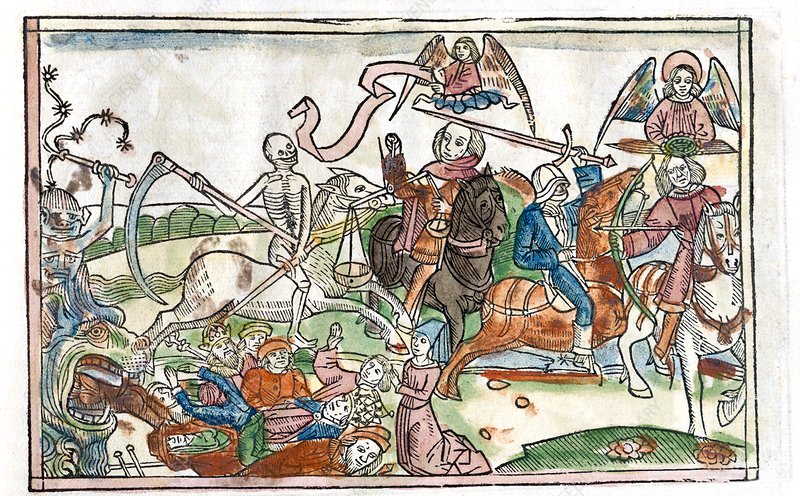

Золотий вік Ізраїлю тривав недовго. Давид побудував царство, Соломон зміцнив і розширив. Але на вершині своєї могутності Соломон втратив майже все. Тисяча дружин і наложниць, море золота, сп’яніння славою погубили царя й царство.

Бог, Який дав йому мудрість, силу йславу, виносить свій вирок: «Тому, що було це з тобою, і не виконував ти Мого заповіту та постанов Моїх, що Я наказав був тобі, Я конче відберу царство твоє та й дам його твоєму рабові» (1Цар.11:11).

І раптом з’являються вороги — Гадад із Едома й Резон із Дамаска. Вони мстять за загибель своїх царств і за успіх Соломонового царства.

Але найстрашніше приходить зсередини. Єровоам, «раб Соломонів, підняв руку на царя». Бунтарів було багато завжди. Але цього разу повстати проти царя закликає пророк Божий.

Пророк Ахійя говорить не від себе: «Візьми собі десять кусків, бо так говорить Господь, Бог Ізраїлів: ось, Я віддираю царство з Соломонової руки, і дам тобі десять племен» (31). Бог дає шанс навіть заколотнику Єровоамові: «Якщо будеш ходити Моїми дорогами…побудую тобі міцний дім, як Я збудував був Давидові» (38). Раніше Він дав всі шанси Соломону, попереджав, нагадував. Тепер Він закликає «мужнього» раба.

Колись мудрий Соломон у кінці життя робить нові й нові дурниці. Він не слухає Бога й намагається зберегти владу будь-якою ціною. Трон хитається, і йому здається: єдиний спосіб зміцнити його — насильство. Тому Соломон шукає, «щоб забити Єровоама» (40). Та Єровоам ховається в тому самому Єгипті, звідки родом Соломонова прекрасна дружина. Навіть союзники стали противниками. Царство руйнується на очах. І Соломона рятує від остаточного падіння лише смерть.

Бог вірний і вберігає Соломона від осоромлення. Він веде Свою лінію через Давида й Соломона, караючи й милуючи, наставляючи й викриваючи їхніх нащадків. Ми — частина цієї довгої історії. І ми чекаємо того Царства, якому не буде кінця.