![‘Maidan theology’ as a sum of ‘little stories’]()

‘Maidan theology’ is a narrative and biographical theology. It is a sum of experience, intuitions, and reflections of people who actually took part in the events. ‘Little stories’ of ‘little leaders’ are not organized into a single text, and yet, they are united by the same values and connotations as well as by the relationships of civil and Christian solidarity.

It all started with civil solidarity. Marina Gogulia, the leader of Christian students and linguist, came to Euromaidan because of her consciousness. “Consciousness. I took part in Euromaidan from the very first evening. On my way from the Opera theatre, where there was a premiere about the Holodomor, I was walking to Maidan. I met people there, who were also upset by the unsigned agreement about the association with the EU. I didn’t want to go into the Customs Union with Russia and under the new control” [2]. Marina served in one of self-defense sotnias and in the Prayer tent. It is on Maidan that she found her Christian community. “On Maidan I met quite a lot of noble people, who were such an example of bravery and sacrifice, which I had never seen before in my life. I was on Maidan in the hardest moments – night on December 11th, in mid-January when we were expecting a night dispersion; February 18th, 19th, 20th …I thought, if they weren’t afraid, I would also feel embarrassed to run home” [2].

After the events of November 30th, there were not only social activists on Maidan but also people who could not stay indifferent. They had neither an action plan, nor a theological rationale. They, however, had the feeling that what was happening really mattered. Elena Panych, a religion expert, admits “I was motivated by two things – love to my motherland and anxiety about its future. Yes, there were Christians on Maidan too, and there even was a tent, where Christians prayed about Ukraine. I think, everyone has a right to decide for themselves, which position to adhere, however, I am sure, that all believers should know and understand as much as possible about what is going on in the country, where they live” [7]. She did not worry about the official position of church leaders. “They either do not fully understand what it was all about, or trying to be diplomatic and politically correct. It is their right and their choice. I think that average church members have different views” [7].

As an answer to the questions concerning the reasons of church passiveness and ‘theology of neutrality’, Panych has suggested some strong points “There is evidence to think, that Evangelical movement, which had been formed on Soviet territory, became an imperial church, therefore, the heirs of this tradition…, unwittingly for themselves became the hostages of ‘russkii mir’. The desire to be liberated from imperial influence of Russia in such setting is considered to be a rebellion against the familiar, and all-in-all legitimate order. It’s not a secret that Evangelical Protestants in Ukraine (not all, though, a majority) were in the rows of strongest opponents of European integration. I visited churches where people prayed about the failure of the agreement of association with the EU. Euromaidan was a surprise for them and made them think over their positions. And still, the tradition to make a contrast with ‘immoral West’ has not disappeared” [18].

It explains that strange dependence of post-Soviet Protestants on Soviet past, when they were repressed. It also highlights the tendency of those churches to maintain the status quo in current discussions about the future of the country. For them the legitimacy was consecrated with the past and any changes are suspicious.

“Most Evangelical Protestant Churches have maintained the status quo in politics. On the other hand, some Christians keep looking at the events in Ukraine with skepticism of ‘post-orange syndrome’. Nowadays a new Evangelical Protestant mindset is being formed, which does not separate processes in the country from the spiritual needs of the nation. Such understanding was based on dichotomic perception of the Church as a ‘spiritual’ part of life, which should by all means avoid any social and political issues. Whether we, as a country, choose an eastern vector or a western one…, what matters is whether we (Christians) will become theomachists because of our unwillingness to take on responsibility for our own nation” [12], with these words the dean of Ukrainian Theological Evangelical Seminary (UETS) Denis Kodiuk expressed his active position.

“So where are the representatives of Christian churches? Why are the leaders of Protestant denominations silent? Is that because they are standing on the foundation of pacifism or it is because any support of oppositional power might have negative consequences for those leaders in future?” [5]. Thousands of young Protestants along with the seminary professor, Anatolii Denisenko, were asking these questions, expecting clarification from their churches. Meanwhile they did realize that they still had the right to disagree with the official position and they had individual responsibility to ‘reconsider their attitude towards the revolution and to look at their Teacher in a new way. Instead of giving a specific answer to the question, whether Jesus would go to Maidan today or not, it is worth asking another specific question: “How do I envision Christ?” Is he a humble lamb or a guerrilla with a riffle on his shoulder? Or maybe someone else? Maybe he was a radical, reformator reformer? and revolutionary, who managed to impact the society he lived in using a non-violent protest against the ruling regime” [5].

Not all people were thinking about the political choice of the country and transformation of the society. Most Christians saw their role in helping the victims and witnessing about God. A seminary student Ekaterina Zhitskaia says, “I considered my mission to be communicating with people and praying with them. I usually said the following: ‘I am neither ‘for’ the EU, nor ‘against’ it. I simply don’t like the way Ukrainian authorities react’. Besides, there were a lot of people on Maidan, who needed God, and to whom it was necessary to show that Christians are really God’s children” [3, 68].

The unity of religious and social motives was demonstrated by theologically educated leaders. “My way to Maidan was both a Christian and civil response. It was clear, just as they dispersed students, they might disperse Christians in the future”, stated a dean of seminary [3, 46]. In this sense, it was inevitable, nonparticipation is understood to be a sin of inertness. “It was a sin not to serve peaceful people on predominantly peaceful Maidan. There were ministers, who stood up between the conflicting sides and, in effect, stopped the fights” [3, 70].

A youth pastor and the founder of Interdenominational Prayer Tent on Maidan, Oleg Magdych prefers to talk about a sequence of motives, their gradual deepening and radicalization of questions. “Motives? When I came, I wanted to help the guys, who had been beaten up. I did not position myself as a pastor, I was a simple man. Of course, we had talks about God. We were still shocked and confused about our further actions. It is then that we got an idea to encourage the nation to pray about Ukraine, since there was enough food and clothes” [3, 32-33]. A bit later we got a missionary motive. “It’s great to be light and salt in our churches every Sunday, but it is not what we’ve been called to do. Jesus came to people. We have to shine in the darkness, and our churches are the places of light. I do not mean that Jesus is not in the church. The tent ministry is much wider and greater than a prayer” [3, 140]. After the mass riots there is going to be a thought that mere presence of Christians on Maidan is not sufficient, they should proactively take part. “After the riots on Hrushevskogo street we started to go to people more. We simply started to go to the places where we saw people. Before that we were sitting in one place and waiting for them to come to us” [3, 203].

As it was stated by one of the founders of the Prayer tent, Oles Dmitrenko “The further ministry of Protestants on Maidan was initiated not by the bishops, nor by the chairmen of religious unions or churches, but by the conscientious young Christians from various churches in Kiev. The absence of prompt reaction, solid position, frankly speaking, made people angry. Popular spiritual teachers and leadership coaches seemed to have vanished. Oleg Magdych, the youth pastor of church ‘Novaia Zhizn’, and marketologist Andrei Shehovtsov, were among the first Protestant activists on Maidan” [3, 54].

He has an interesting story of how prayer and politics are connected. “From its very first day, the tent became a symbol of God’s presence on Maidan. The first visitor of the tent was Yurii Lutsenko. He was excited, anxious and earnestly asking ‘Fellows, I beg you to pray. The situation is serious. We need God’s protection’. While bishops were waiting…., a politician desperately called for prayers” [3, 55].

Apparently, God of bishops and God of students were not the same. According to the opinion of an 18-year old student Karina Fedoricheva, “If it wasn’t for the prayer tent, many people would not hear the news about the kind and proactive God, who has nothing to do with the widely spread stereotype about him, as an ‘old man in heaven’, indifferent to human life” [3, 106].

Indifferent bishops were quite content with the ‘indifferent old man in heaven’. The Church was mostly represented by individual Christian activists. The leader of Christian students Denis Gorenkov admits that “the hardest times for me were during the riots. I still remember clearly well several nights in the end of December. It looked like the morning would never come. There were few people, desperation was in the air. My friends kept talking about the coming defeat of Maidan. I stayed there and kept praying, since I really didn’t know what else I could do, if not pray” [3, 119].

Often the circumstances (that is, God through circumstances) showed what to do and mobilized the people. “On the 22 of January in the morning I saw on the news that three Orthodox monks were standing between the opposition and the Berkut police. I immediately realized that my place was with those monks. It was the best day of my life” shared his experience Denis Gorenkov [3, 172].

Such emotional responses were not rare for those days. In the morning of the 19th of February, after the bloody riots at night, Taras Diatlik recalled the cheerful sunrise among those whose sufferings continued. “That was the second most joyful day of my life, which could be compared only with the joy before the dawn on the day of my wedding 21 years ago. Deep dark night was over, prayers of God’s children, no matter what denominations they belonged to, on Maidan and throughout the world hadn’t ceased for the whole night. Maidan remained. For everyone it was a trial from God. A trial of love, humanness, compassion, comfort, friendship, cooperation, unity in Christ, and simply a trial of human involvement, faithfulness to the truth, God’s values, philosophy of theological education, the essence of sermon, counseling” [6].

The experience of Maidan events and discussion concerning the Church attitude towards the current events were expressed not so much in a new understanding of community as in re-thinking about the Church, its theology, power and ways to treat the Bible. Biblicism and fundamentalism lost their positions, did not pass the test of Maidan. Direct Biblical quotes, taken away from their contexts, served as justification of the illegal authorities and crimes against humanity. Nowadays some young theologians say that “Bible reading should be constantly accompanied by our pondering about our time. It will help to correlate the Gospel with the modern life and to deepen our understanding of the Gospel and of life. Gutiérrez theology at its core is religious commentaries of political events. Can it be the true nature of theology? Such a hermeneutical method leads to the conclusion that theology is not orthodoxy, but an endless critical perception of practice – orthopraxy” [4].

Young leaders read the Bible in a different manner than the leaders from Soviet generations. They saw in the Bible the foundation for active civil position and church nonconformism. There were three claims which became the visible signs of group solidarity of the ‘little leaders’ of the Evangelical community. Those three claims were of somewhat discomfort for the formal leaders of confessions, who presented an alternative socio-theological positions. The first public statement appeared on 11th of December 2013 as an open letter addressed to the Evangelical community of Ukraine. The letter of the ‘disagreed’ questioned the statement of Viacheslav Nesteruk, the president of All-Ukrainian Union of Associations of Evangelical Christians Baptists (AUA ECB), that “there is no our activeness on Maidan”. “Such opinion simplifies social position of ECB and brings it to the extreme ‘neutrality’, as if the Church were able to live somewhere in a neutral zone, outside the society and its questions or needs. It’s worth remembering that from its very beginning the Baptist Church was standing for the values of freedom and justice. The first leaders of the Baptist movement presented a quite clear social requirement “The Free Church in the free state”. Independence of the Church from the state (the seventh Baptist principle) does not imply that the Church is isolated from the community, nor does it mean that the Church is apolitical or asocial. Evangelical Christians cannot stay ‘neutral’ when the state officials abuse their responsibilities, when the students’ blood is shed, judges make non- lawful decisions, and internal security forces protect the authorities instead of the nation. Involvement in meetings is an individual responsibility of believers, such responsibility is not separated from faith and expresses faith through a civil position. ECB churches do no call for political actions, nor for the violence, instead, they encourage a responsible choice of every individual, take care of the suffering and unfairly accused” [1].

The letter was signed by the leaders and theology professors of ECB theological academic institutions: Nikolai Romaniuk, Mikhail Cherenkov, Anatoliy Prokopchuk, Sergei Timchenko, Fedor Ratchinets, Aleksander Geichenko, Denis Gorenkov, Taras Diatlik, Denis Kondiuk, Kostantin Teteriatnikov, Valentin Sinii.

The discussion went outside the walls of the Baptist Church and had its effect among other Evangelical churches. In this case it is noteworthy to hear a woman’s voice, a brave opinion of a psychotherapist Natalia Prostun. “It seems to me, there is a bureaucracy system even in the Protestant movement. While the leaders were arriving at the decision whether Christians should be on Maidan or not, others had already been helping on Maidan. I feel ashamed as I am identified with the Evangelical faith. As a Christian, I understand that I would like to see heroes among Evangelical pastors. When Viacheslav Nesteruk wrote ‘there are no Baptists on Maidan’ I started to think about the herd instinct of believers” [3, 212].

In the following month the group of disagreeing with ‘neutrality theology’ increased and became interdenominational, involving almost all Protestant denominations. On the 21st of January 2014 there was the “Appeal to the Evangelical churches of Ukraine” composed by the members of the round table ‘Maidan and the Church: mission and social responsibility of every Christian’. It was addressed to ‘the leaders of church unions, ministers, ministry leaders, and laymen of the Evangelical churches in Ukraine with the appeal to use all possible means to protect the truth and justice in our country” “in the context of the latest events (oppression of activists on Maidan, threats to Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, accepted anti-constitutional laws on the 16th of January and armed riots of the 19th of January 2014)” [16]. The initiative and the text of the appeal belonged to young leaders of the Prayer tent on Maidan (Andrei Shehovtsov and Oleg Magdych), Fellowship of Evangelical Students (Denis Gorenkov and Eugenii Shatalov), Ukrainian Evangelical Theological Seminary (Petro Kovalich and Denis Kondiuk), and the Association for Spiritual Renewal. As the authors mentioned “The Church fairly avoided any political speculations concerning the issue of the association with the EU. But after the blood was shed on November 30, 2013 on Maidan, the Church cannot stay neutral any more. Because of its moral responsibility before God and community the Church has to call that bloody riot against the peaceful citizens a crime, and we express the demand of the nation to respect the freedom, dignity and human rights. The authorities should fulfill their constitutional responsibilities for the common good and not to abuse the power. The Church adds its authoritative word to the voice of the people by reminding the dignity of man, created by God and in God’s image; all people are equal before God; there is law and there will be judgment for all people; there is God intercedes for the unprotected. Meanwhile, the Church reminds the authorities and the Protestants about God’s love commandments, without which the demand for justice can end up in chaos and violence. We believe that by God’s mercy, our prayers, counseling, and the work of Christians the events on Maidan will be the beginning of the spiritual renewal and restoration for the whole Ukrainian nation” [16].

On the 20th of September 2014 the resolution of the round table ‘Church in war conditions: theology, position, mission’ was published. It was addressed to ‘the Evangelical churches of Ukraine and international community with the appeal for active help, spiritual solidarity, constant prayer about peace and protection of Ukraine from Russian aggression, about solidarity of Ukrainian churches and revelation for our Russian brothers’. “The war tests theology, position and mission of Ukrainian churches, brings about repentance and re-evaluation. Until recently local Christians emphasized pacifism and indifference towards politics. In the Soviet context, when the state was atheistic, non-participation in ‘politics’ was a passive form of protest. Hardly anything has changed since then. For the twenty-three years of Ukraine’s independence this issue has never been discussed, therefore, the events on Maidan, following the annexation of Crimea and the war on Donbass, posed an unprecedented challenge for the Church and its social position. References to the past are outdated, and the ‘wise’ silence no longer helps. It is time for the Church to shape its attitude towards war and peace, state, community and social responsibility. First, Evangelical theology does not approve any indifferent attitude toward wars, which are the greatest tragedy of humanity. We cannot contrast spiritual vocation with civil responsibility of Christians. On the contrary, Christian vocation is embodied in the forms of civil participation. The contrast between the Church and society, religion and politics, does not have any biblical foundation. Second, under the conditions of military mobilization the Church should take the position of compassion and activeness. The Church can no longer be a passive observer, and simply express ‘its anxiety’ and good intentions for ‘peace’. Church ministers should be everywhere, where people are suffering or dying, including the frontlines. If Christians accept the call to protect their homeland with a weapon, they should follow that call. Third, the field of war should become the field of mission, of reconciliation, restoration and forgiveness. In such critical period of Ukrainian history the Church like never before should be close to people in order to serve them, and along with them to serve the country” [19].

This resolution is remarkable in the sense that it reflects a turning point of how Evangelical community views the war. Earlier on the 13th of June 2014 the delegates of the AUA ECB convention under the pressure of the adherents to the ‘neutrality theology’ (Sergei Sannikov, Gregorii Komendant, Viacheslav Nesteruk among them) refused to accept a similar resolution (I co-authored that project). In September (after the summer fights, shed blood, the occupation of Donetsk by military divisions of Girkin, and ‘Ilovaisk Kettle’ ) the resolution of the round table mentioned above caused not as much opposition, as jealousy among the ECB leaders. On 20-21 November 2014 all-Ukrainian pastor conference of AUA ECB was held. It had the same title – ‘The church under conditions of war’ and it supported the main points of the past resolutions.

Such a coincidence may be an illustration of the provoking statement by Anatolii Denisenko, that “professional academic minority takes place of the fundamentally minded church majority” [4]. At least, one should admit that this minority already has the initiative, defines the theological agenda for the Church and even wider – for the whole civil community and relationships between the Church and the community.

Informal leaders of the Evangelical community and their positions had emerged much earlier than the official leaders of Protestant denominations stepped in and stated their ‘position guidelines’. As it was remembered by the participants of the events, “The organizers on the stage often asked to send someone from the Protestants for the night prayer, to share God’s word, but bishops weren’t there. Therefore, the huge Protestant movement of Ukraine almost every night was represented by….a tiny seminary student Katia” [3, 86].

The difference, however, is obvious not only in the response speed; it is even more shown in the theological mindset of Soviet-generation and of post-Soviet one.

While the official leaders quoted chapter thirteen of the epistle to Romans thoughtlessly, Christian lawyers defined, that “the institute of power itself is from God, but any particular figure at power is not always from God. God has given people the right to choose, but our choice does not always correspond with God’s will” [17]. A more thorough critical hermeneutics of Romans 13 was suggested by the professor of theology Petro Kovaliv. “To obey the powers is not the same as to bear the injustice. So, if the authorities decide to take the criminal way, we should declare our protest, instead of punishing the criminals. Besides, we are to keep in mind, that the structure of Ukraine significantly differs from the structure of the Roman empire, when New Testament authors wrote the epistles. According to the Constitution of Ukraine (article 5), the highest power belongs to the people. Therefore, the authorities are held responsible not only before God to serve good people and punish criminals, but also before the nation, that elected them. The people have the right to estimate what authorities do and to replace them. Such a civil position does not only correspond with the Bible and the laws of Ukraine, moreover, it is absolutely supported by the Bible and the state laws. Christians came out to express that position and that protest” [11].

At the same time the scholar highlights ‘the right methods’, ‘the radical character of Christ’s love’ and non-violent nature of the protest. “That is exactly what protestants did, when they brought tea and food to the hungry and cold policemen, when they did not revenge the policemen, who had been caught during the riots on Maidan on the 11th of December, and let them leave through the human corridor; when they shared food with the (deceived by the authorities) members of Anti-Maidan and later helped them return home” [11].

This new ‘hermeneutics of freedom and responsibility’ gained more and more influence, in particular on the pages of official church publications. A pastor from Rivne, Ivan Mikhalchuk, candidly wrote “Many Christians of post-Soviet countries, due to historical reasons, explain their indifference to social life or to expression of active civil position, referring to the passages from the Bible, e.g., ‘Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established’ (Rom. 13:1, NIV). Now, let us approach this question from another perspective. If the authorities make such laws that, as a matter of fact, contradict with God’s principles, how should Christians respond? Or what should Christ’s followers do when the authorities do not follow the laws which they themselves established, do unfair judgment, steal from the poor, offend orphans? Strangely enough, Christians are not able to adjust to the system, which, on the other hand, they use to claim that they are outside the politics, or to talk about fully obeying the authorities according to the Bible. Still on the other hand, Christians justify their actions, claiming that circumstances of this country make them give bribes. Doesn’t it sound hypocritical? In the times of Old Testament some kings were far from doing justice and living according with God’s will. Still there were prophets who told them the truth. The Bible has a plenty of such examples. Isn’t it one of the objectives of the Church in the times of New Testament, to act righteously and do justice? Telling the truth to the authorities and motivating them to act rightly has nothing to do with being disobedient to the authorities” [15, 12].

Not all these ideas were immediately accepted, though. At first, the ideas of the ‘little leaders’ were rejected, then criticized, and only when things calmed down, they were accepted, as a sign of a new developing church consensus. It is well known that during the period of stability generation differences are smoothened, while in the period of crisis they are aggravated.

While one of the bishops was bragging that he had not read the Constitution, since the Bible is better, the leader of Alliance of Christian Professionals, Sergei Gula, publicly objected that. ‘It is irresponsible to know only God’s law and not to know state laws” [17].

Whereas most Evangelical pastors were obsequiously praying about kings and were unaware of their civil rights, a youth pastor Oleg Magdych was calling to “the war with ‘sovok’ in the Church’ “Even the majority of people who came out to Maidan still have ‘sovok’ in their heads. People don’t know basic things about society and individuality…We have a wry look at the authorities. It is the beginning of the war with sovok in our Church” [17]. Pastor Nikolai Romaniuk wrote about the very same thing, “My Scripture meditations have brought me to understanding that God does not place presidents, premiere ministers or mayors, neither does he put directors or even pastors, we, people, members of communities, elect them. Pondering over the history of the fascist Germany, I can assert that indecisive, agreeable, fearful and ‘covering’ policy of a large group of pastors and priests granted Hitler the right to do whatever he wanted to. It is bad that the disorders of society have been transferred onto believers and ministers of Evangelical Christian Baptists (in particular). We have a chance to critically reconsider what went wrong with us, repent, and do our best to spread the Kingdom of God in Ukraine in a more rapid way” [3, 10-11].

While the official leaders of church unions even refused to pronounce the word ‘war’, hundreds of Protestants went to serve to the troops, because they envisioned God’s presence not only in the Church, but in the war as well. Simple words of one of the chaplains can serve a good example of that intuitive theology. “You don’t need to run away, you don’t need to be afraid. You need to pursue God in your life. You need to bust the myth that it’s better to go to prison than to war. I never served in army. But now God is calling me. Unknown things are always frightening, but I don’t want to avoid God’s order, like Jonah did, so that later I do not come back ashamed. I do worry, but with God I will go anywhere. I am a little part of God’s great plan and I rejoice that God has honored me to be with soldiers and to represent God among them. I do not support the war, I support the soldiers” [9].

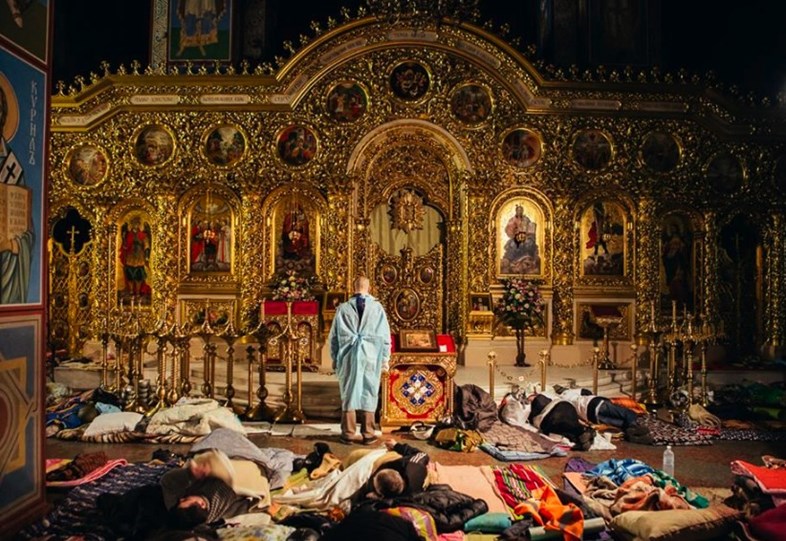

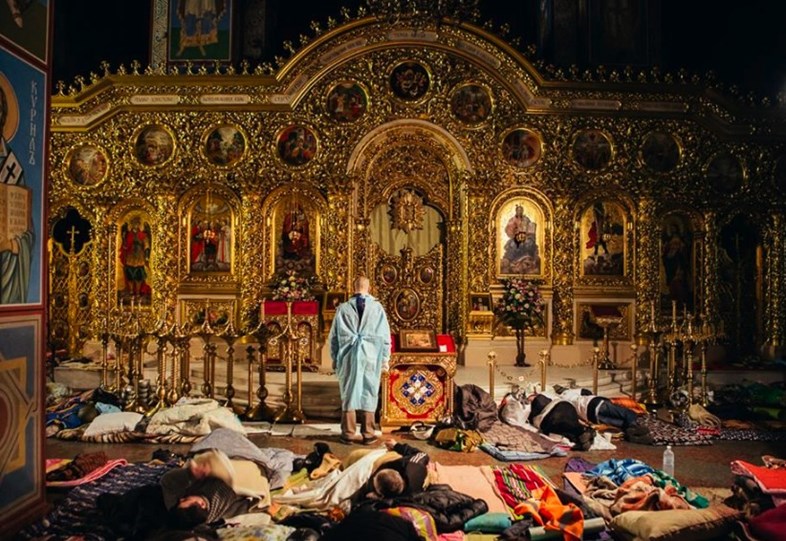

However, the basic and important difference between the field leaders and the office leaders was that the first ones got involved, while the second ones were watching. This very fact changes the perspective. “I was hurt that Orthodox Christians, Rome Catholics and Greek Catholics prevailed on Maidan in number. These people have felt and still feel cold shoulder attitude of the Protestant church because of the ritual issues. It is those people who responded to the needs of the protesting people, confessed them, prayed with them. It hurt me that the Protestants, who were well-known for their friendliness toward people and outreaches, weren’t there with those people who desperately needed help. And mere Orthodox priests lived with them and spent days and nights. In that I saw God’s reply to the question, whether the Church can be separated from the state. I did understand that the Church is separated from the state, but the Church without people makes no sense. Unfortunately, I wasn’t proud of the image of the Protestant confessions” [3, 256], admits the activist of medical service of Maidan, Lesia Kotovitskaia. She elaborates, “I saw that Protestant churches have woken up. But they did it only after the bloody morning” [3, 271].

Similarly, another participator of the events, student Ekaterina Zhitskaia, shares her opinion, “Protestants could have done much more. Unfortunately, there were too many people among ourselves who insisted on praying only at home and in church” [3, 273].

A theologian Denis Kondiuk thoughtfully concludes, “Did the Protestants use the chance of sharing the Good news on Maidan? Yes and no. Young churches with young leaders showed proactiveness, ability to respond to what was happening and open to new things. These ministers were not afraid of trying, searching, and taking risks. On the other hand, more experienced and respectful Ukrainian Protestant denominations seemed not to notice Maidan for some period…they waited, watched and thought what to do” [3, 69].

To be continued