![РОДОВЫЕ СХВАТКИ НОВОГО МИРА]()

Журнал «Вера и Жизнь», 2016, №1

Вопрос учеников нам кажется необычайно актуальным и понятным. Как и они, мы чувствуем тревогу, потому что рушится привычный мир, наступает хаос. Как и в то далекое время, мы спрашиваем: как понимать происходящее, как узнать наступающий конец, как предвидеть и подготовиться? Мы хотим знать признаки и сроки. Но в ответ слышим: «Берегитесь, чтобы кто не прельстил вас».

Главный признак

Нам кажется, что Христос уходит от ответа, но это и есть Его ответ. Он хочет, чтобы мы следили за собой, бодрствовали. Для Него это важнее всего прочего – важнее любопытных фактов, подсчетов, расследований и споров.

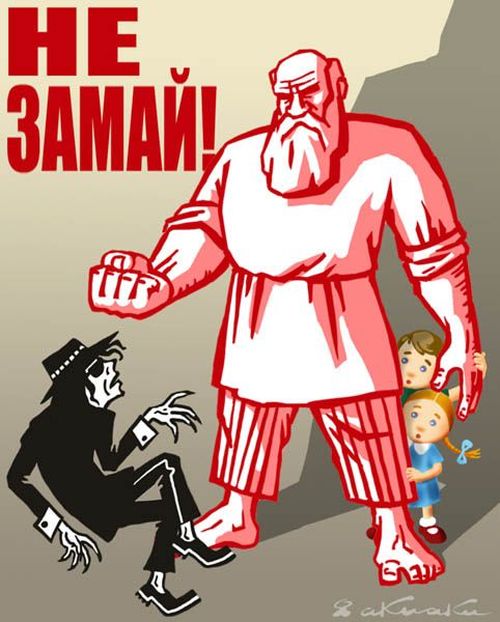

В то же время в Его совете беречься обольщения есть прямой ответ на вопрос о главном признаке последнего времени. Обольщение и есть главный признак конца. Обольщение – это сладкая, приятная неправда. Обольщают с коварной улыбкой и при этом ничего не требуют, кроме согласия на ложь, измену и отступление.

Конечно, обольщение угрожало всегда, но сейчас оно достигло немыслимых масштабов. И это сближает наше время с пророчеством Христа, когда подавляющее большинство будет служить лжи и преследовать тех немногих, кто останется верным истине. «Тогда будут предавать вас на мучения и убивать вас; и вы будете ненавидимы всеми народами за имя Мое; и тогда соблазнятся многие, и друг друга будут предавать, и возненавидят друг друга; и многие лжепророки восстанут и прельстят многих; и по причине умножения беззакония во многих охладеет любовь. Претерпевший же до конца спасется» (Мф. 24:9–13).

Немногие

Обратите внимание, как часто в этих стихах звучит слово «многие»: многие соблазнятся, многие возненавидят, многие предадут, многие охладеют в любви. А «претерпевший» – в единственном числе. Верный всегда почти один, верные всегда в меньшинстве.

Эта диспропорция, разительный контраст между многими и немногими, толпой и единицами – признак последнего времени. Если вы видите вокруг себя, как большинство легко соглашается с неправдой и грехом, можете быть уверены: конец близок.

Немного социологии. Как говорят исследователи, для того чтобы какая-то социальная группа стала влиятельной и могла изменить общество в целом, ей нужно достигнуть 5% от общей численности. На сегодня численность евангельских христиан в постсоветских странах колеблется в пределах 1%. Евангельские верующие – явно в меньшинстве.

Ответственность каждого

Массовое обольщение должно нас страшить куда сильнее, чем война. Почему? Потому что война, как правило, не в нашей власти, а вот поддаться или не поддаться обольщению – наша ответственность.

Вот почему Христос предупреждает о соблазнах и лишь затем продолжает разговор о войнах и прочих бедах: «Также услышите о войнах и о военных слухах. Смотрите, не ужасайтесь, ибо надлежит всему тому быть, но это еще не конец; ибо восстанет народ на народ и царство на царство; и будут глады, моры и землетрясения по местам; всё же это – начало болезней» (Мф. 24:6–8).

Цена истины

Христос предупреждает, чтобы мы следили не за внешними событиями, но за собой, потому что основная угроза исходит не от духа войны, но от духа обольщения. Жертв пропаганды намного больше, чем жертв войны.

На фоне всеобщего сна те немногие, что бодрствуют, должны свидетельствовать об истине. «Но вы смотри?те за собой, ибо вас будут предавать в судилища и бить в синагогах, и перед правителями и царями поставят вас за Меня, для свидетельства перед ними» (Мк. 13:9).

Свидетельство – отнюдь не легкий и веселый рассказ о бытовом происшествии, не шоу и аплодисменты, не сладкая вата и развлечения. Христианское свидетельство связано с му ченичеством. Это когда я свидетельствую о том, что только Христос – Господь, что истина – не мнение большинства, а Его воля. Как вы понимаете, это не нравилось многим и раньше и не может нравиться сегодня. Именно за это первых христиан распинали, отдавали на растерзание зверям. Именно за это можно поплатиться головой и сегодня.

Когда большинство называет черное белым, когда об истине молчат, когда страх парализует, тогда свидетельство верных и бодрствующих приобретает особую ценность. Я уверен, что Бог готовит нас не для тихих и мирных времен, но для дерзновенного и мужественного свидетельства во время массового отступления.

Свидетельство всем народам – это не только распространение Евангелия в мирное и спокойное время. Свидетельство прямо связано с войнами, катастрофами и преследованиями. Свидетельством будет мудрое и терпеливое поведение христиан среди бедствий. На фоне всеобщего обольщения они будут хранить здравый смысл и верность Христу. Они не позволят манипулировать собой и они не будут торговать своими убеждениями. Они будут отделять истину от лжи и провозглашать ее смело и громко.

Поручение

То, что нам довелось жить в дни массового обольщения, – не трагедия, а привилегия, Божье доверие и поручение, возможность послужить сонным людям отрезвляющим словом истины. Мы нужны Ему, и Он готовит нас: «Я дам вам уста и премудрость, которой не возмогут ни противоречить, ни противостоять все, противящиеся вам» (Лк. 21:15).

Мы знаем, что «проповедано будет сие Евангелие Царства по всей вселенной, во свидетельство всем народам; и тогда придет конец» (Мф.24:14). Но что будет представлять собой эта проповедь? Не только и не столько телепередачи, глянцевые журналы, подарочные издания Библии, концерты и крусейды. В первую очередь понадобится смелое слово мученика, разгоняющее тьму и открывающее правду, обличающее сговорчивое большинство и прославляющее единого и единственного Господина. Лучшим свидетельством древнему Риму, искавшему лишь хлеба и зрелищ, был крик умирающего, но несломленного христианина: «Иисус – Господь!» Лучшим свидетельством современному миру, одурманенному пропагандой и потребительством, будет все то же слово: «Иисус – Господь!» Это смелое исповедание вызывает ненависть мира, но именно оно властно касается открытых сердец.

Путь обольщения Господство Христа оспаривают не только мечом, но и полуправдой, не только угрозой, но и прелестью. Основная опасность обольщения не в том, что люди ошибаются, не разбираются, не понимают. Каждый из нас может запутаться, обмануться в своем выборе, но если не следить за собой, то ложь усиливается и губит. Самое страшное, что обольщение ведет к измене Христу и Его Царству. Все, вступившие на дорогу лжи, рано или поздно принимают ложь за правду, антихриста за Христа, князя мира сего за Господа.

Нам начинает казаться, что «Царство, и сила, и слава» принадлежат не Богу, потому что Бог далек, а дьяволу, так как он ближе и полезнее. Иногда кажется, что то, что мы так долго просили у Бога, может легко и быстро дать дьявол или его слуги. Тогда вместо Христа мы начинаем поклоняться антихристу.

Нас обольщает искусство пропаганды, очарование разврата, власть зла, рейтинги, самоуверенные речи, популизм, подтасовки, красивые картинки, мнения экспертов, обещания и победы. Однако стоит помнить предупреждение Христа, что лжехристы придут под Его именем, что зло не будет называться злом, но вырядится в светлые одежды. «Ибо восстанут лжехристы и лжепророки и дадут знамения и чудеса, чтобы прельстить, если возможно, и избранных. Вы же берегитесь. Вот, Я наперед сказал вам всё» (Мк. 13:22–23).

Внутренний враг

Гонения придут не только извне. Разделение и вражда проникнут в среду верующих людей. «Предаст же брат брата на смерть, и отец – детей; и восстанут дети на родителей, и умертвят их. И будете ненавидимы всеми за имя Мое; претерпевший же до конца спасется» (Мк. 13:12–13). На самом деле удивляет не сила зла, а то, что зло может обольстить даже добрых людей. Беспокоит не столько число и жестокость врагов, сколько предательство друзей.

Точно так же, как вместо Царя будут лжецари, вместо Христа – лжехристы, так вместо Церкви будут церкви-подделки. Конечно, люди будут чувствовать разницу и обман, но далеко не каждый захочет рисковать своим благополучием или своей головой, задавая «лишние вопросы».

«Следить за собой» означает утверждаться в здравом евангельском учении, сохранять единство и общение с верными, распознавать духов, не участвовать в делах тьмы и обличать их. Все это укрепляет в нас иммунитет к пропаганде.

Сила верности и радость победы

Бодрствующий христианин задает себе вопрос: «Кто мой Царь?» Бодрствующий не разменивает себя на мнения и сенсации, не смотрит телевизор до головокружения или умопомрачения. Он следит за собой, сверяя себя с Христом, не теряя Его из виду. Он боится одного – остаться без Христа, изменить себе и Ему.

Кто боится Бога и больше всего ценит верность Ему, тот не будет бояться войн и военных слухов, гонений и бедствий. «Начало болезней» он воспринимает с радостью, потому что эти «болезни» не к смерти. Это родовые схватки, в которых приходит Царство Божье.

Многим кажется, что в болезнях умирает все доброе, что еще есть в мире, но это не так. Мир болен муками рождения! Рождается новая эпоха – Царство Божье, которое прорастает изнутри, как семя, заквашивает мир, как закваска. Христианин не боится «начала болезней», так как знает, что в них рождается Царство. И войти в это Царство смогут те, кто не поддался обольщению, кто не изменил Царю.

Участником наступающего Божьего Царства станет лишь тот, кто исповедовал господство Иисуса, кто верил только Евангелию, кто не стыдился истины и «не сообразовался с веком сим», но свидетельствовал своей жизнью