risu.org.ua

March 24, 2017

Marking the jubilee of Reformation this year, one should think not only about their Reformation, but also about our Reformation, about ourselves, about the relationship between Western and Eastern Christian traditions, between Europe and Ukraine.

Ukrainian culture maintained controversial perception of the Reformation. There was unanimity only in one thing: The Reformation is a meeting with the other Christianity and the other Europe. But the meeting could be detrimental or or beneficial, friendly or conflict-fraught.

For the mass consciousness influenced by orthodox ideology and culture, the Reformation was similar to attacks on other people’s territory, a dangerous plague. Martin Luther was called the Furious (sounds “Liuty” in Ukrainian): “He was truly called Luther (Liuty), as he told ‘furious’ heresies.” What kind of “heresy” were these, that represented a different image of Christianity and its relationship with the government, still remains unclear. But this “otherness” was enough to see the Reformation as a threat to the state, church and public safety. Is the freedom of conscience not a heresy? What if everyone starts to read and interpret the Bible? How can one criticize the Holy Church? Is it possible to change the order of things, which God has established?

“Martin the Furious” was not just different, he was strange, alien, frightening. The Reformation was seen as the Antichrist’s trick of the last days, as a sign of doomsday coming.

The intellectuals saw the Reformation differently. Mylkhailo Drahomanov spoke longingly of the Reformation. For him the whole Ukrainian history was the history interrupted (“cut short”), and the history of Ukrainian Reformation was the history of the Reformation interrupted.

Ukraine could grow with Europe if our Reformation did not fail. But instead of the Reformation there is a yawning gap in Ukrainian history, “rupture and ruin.” Drahomanov expressed these thoughts in connection with the characteristics of Shevchenko, who was not pro-European and revealed the remains of patriotism in the peasantry.

Drahomanov himself hardly saw any prospects in the rebellion, but rather in the pro-European urban culture and the reformed Church. Without the Reformation – “rupture and ruin,” the official church and the destructive Haydamaki movement were to happen. While the Reformation was the return to the European path of development, church renewal, broad civic movement.

While Drahomanov saw the Reformation as a certain mandatory point in history that cannot be escaped, to which one will return one way to another, according to Hrushevsky it was a driving force, “The Ukrainian ship was sailing under full sail to the wind of Reformation and lowered the sails when the wind quieted down and there were no these brave allies, nor their cheerful examples!” [1].

For him, “the wind of the Reformation” quieted down and Ukraine itself was able to do nothing about — historical circumstances changed. While the wind was blowing, there was a unique opportunity to change course and move in the right direction. The wind quieted down – and a chance was missed. Interestingly, before the wind quieted down, the Ukrainians had feared the “conflicting currents of the turbulent era” and had thrown the “anchor” not daring to “establish closer contact with the evangelical movement” and break away “from the Orthodox tradition, from the slogan of the ‘Russian’ national church, from the Patriarchate, who served it and the entire tradition as an anchor in deep waters.” [2]

However, not all chances were lost. Some reforms succeeded. Our contemporary, Harvard historian Serhiy Plokhiy reminds us about it in his new book «Gate of Europe». If Ukraine is the “Gate of Europe,” it combines different worlds, including various Christian traditions. It is not only the “gate” but also the “bridge” (when the gate is open). According to Plokhiy, in Ukraine the “East Reformation” had taken place, which created the Greek Catholic Church and refreshed the Kyivan Orthodoxy, therefore as a result of reforms and fight for various development options, a new pluralistic political and religious culture emerged, allowing discussion and disagreement.” [3]

Surprisingly, besides the Greek Catholics, who synthesized the Eastern and Western Christianity in the national spirit, the historian fails to see the independent role of Protestant communities, as if the “East Reformation” dealt only with Orthodoxy.

Let it be so, the later history showed the failure of the “Orthodox Reformation» and again gave Protestants a chance. What the first wave of Calvinist Reformation failed to achieve, the leaders of second wave — Stunde Baptists achieved. The latter formed an influential community, inscribed it into the confession map and made their version of Protestantism an integral part of Ukrainian national identity. They again caught “the wind of Reformation” and continued “the interrupted history.”

Our “second wave” Protestants were special. Analyzing Protestantism according to Max Weber, the Ukrainian Protestants could not be identified. They never opposed capitalism. They were not engaged in disenchanting of the world. They also did not read Calvin properly. No doubt they learned the basic truths of the Reformation, but rather intuitively than from books.

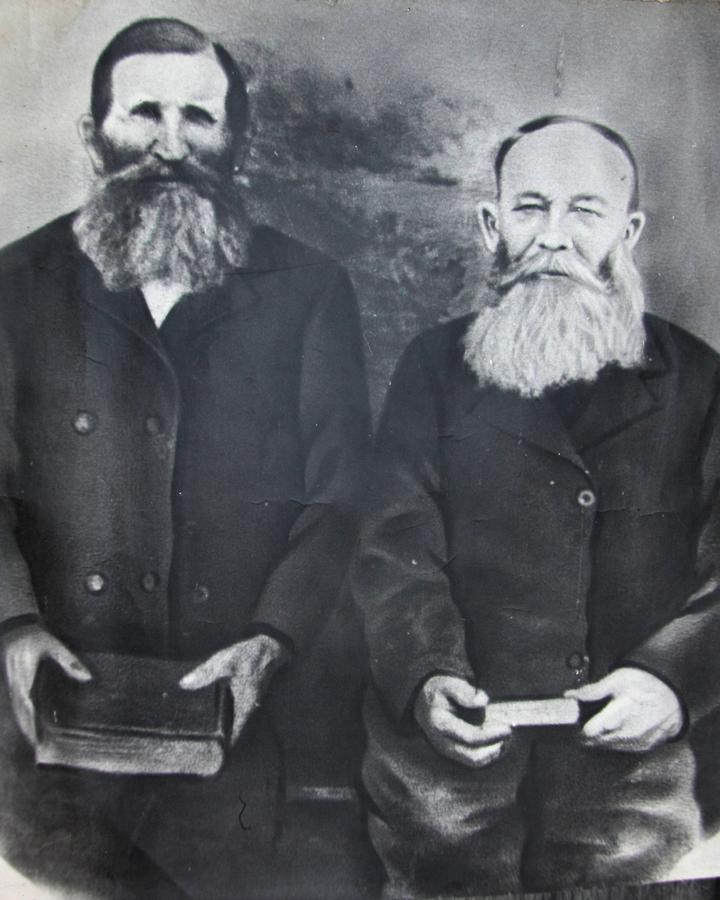

Although books played their role, as did the relationship with European Protestants. This influence can be best seen in the story of Ivan Ryaboshapka — the “Apostle of Baptism in Ukraine.” Lutheran colonists told a peasant from Lyubomyrka of the importance of the Scripture and personal relationship with God. In the same colony Ryaboshapka purchased two copies of the New Testament – for himself and for his friend. He learned to read the Bible and began attending the classes of colonists — the so-called “Bibelstunden.” In 1870 he received “water baptism in faith” by Yukhym Tsymbal, who had been previously baptized by German Baptist preacher. And then he began to baptize other Ukrainians and go preach the “good news.”

Ryaboshapka was a participant of numerous important events. One of them took place in Ryukenau colony in 1882 – at a joint congress of German and Ukrainian Baptists. Other – in 1884 in St. Petersburg, where he represented South Russian Baptists at the convention of the evangelical movement and was nearly left outside due to his peasant outfit.

The farmer-presbyter was distinguishable against the background of both evangelical aristocracy and the Orthodox priesthood. Together with several preachers Ryaboshapka composed the “profession of faith” (1880), which covers both Orthodoxy and Baptism. One of the clauses reads: “We recognize that everything said in the symbol of the Orthodox Church is correct and agree with everything, because everything there is in line with the Scriptures.” Another paragraph says: “We do not recognize anything that is not written in the Holy Scripture.”

Confessing the water baptism in the faith, Ryaboshapka would not speak about it any longer, but about the future life in the community. “The new members are admitted by the majority vote, if the community sees that the new member who seeks to join, has a new life and living faith in Christ. A new member, entering the community, promises to undertake all deeds mentioned in the Holy Scripture (1 Peter 4:18).” The Catechism reminded about discipline – and the possible exclusion and renovation. “A new life and a new faith” were not only to be discovered once, but were to be constantly maintained and warmed – despite persecution. Stunde Baptists became known not only because of their sectarian ‘heresy’, but also due to their diligence, sobriety, strong and large families, mutual aid, biblical literacy.

The Church in Lyubomyrka assembled in the barn, though it counted up to three hundred members. Remarkably, this barn was built with the financial participation of the well-known evangelical Christian and aristocrat, Colonel Pashkov, who had previously received Ryaboshapka in St. Petersburg.

An inconspicuous village of the Tauride province became a hotbed of powerful evangelical movement. The Lutherans awakened the Orthodox. The cause of Wittenberg professor was continued by the Ukrainian farmer.

The second wave of the Reformation in the Ukrainian lands embraced and awakened the peasants. The influence of German colonists gave rise to broad spiritual movement of “Stundists” who studied the Bible in groups and received water baptism “in the faith,” that is, once again in adulthood. The persecution by the tsarist government and the official church led to the fact that yesterday’s Orthodox peasants realized themselves as a separate ecclesiastical community akin both to Orthodox tradition and the Western Baptists. Later this separation of Ukrainian Protestants from the state and the state church deepened and become part of their social and theological identity.

Obviously, the two “waves” of Protestantism in Ukraine could not radically change status quo in cases of dominant denominations and society as a whole. They have created specific types of Protestant denominations (respectively, elitist and marginal), but did not achieve a larger national scale. There is a request for the “third wave” that would change the Orthodox Church and guide the Protestant community back to the church-level transformation. The question remains whether the new reformation will take place under the sign of reconciliation and unity around the Gospel. This question should be answered both by Protestants and Orthodox. For Ukraine, the response of the latter is critical. What will become of Orthodoxy, with its “rupture and ruin”? Will it dare to take off the “anchors” and go in the future? Will it dare open the “Gates of Europe” and meet Martin “the Furious”?

[1] Грушевський М. З історії релігійної думки на Україні [Hrushevsky. From the history of religious thought in Ukraine]/ Kyiv: Osvita, 1992. – p. 79.

[2] Ibid. – p. 78.

[3] Плохій С. Брама Європи. Історія України від скіфських воєн до незалежності [Plokhii S. Gate of Europe. History of Ukraine from Scythian wars till independence]/ Kharkiv, 2016. – p. 139.