The book review for THE JOURNAL OF ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY (October 2017)

Josyf Slipyj. Memoirs / Eds. Ivan Dats’ko, Maryia Horyacha, 2nd edition. Lviv-Rome: Vidavnytstvo UKU (UCU Publishing House), 2014. — 608 p. + 40 ill.

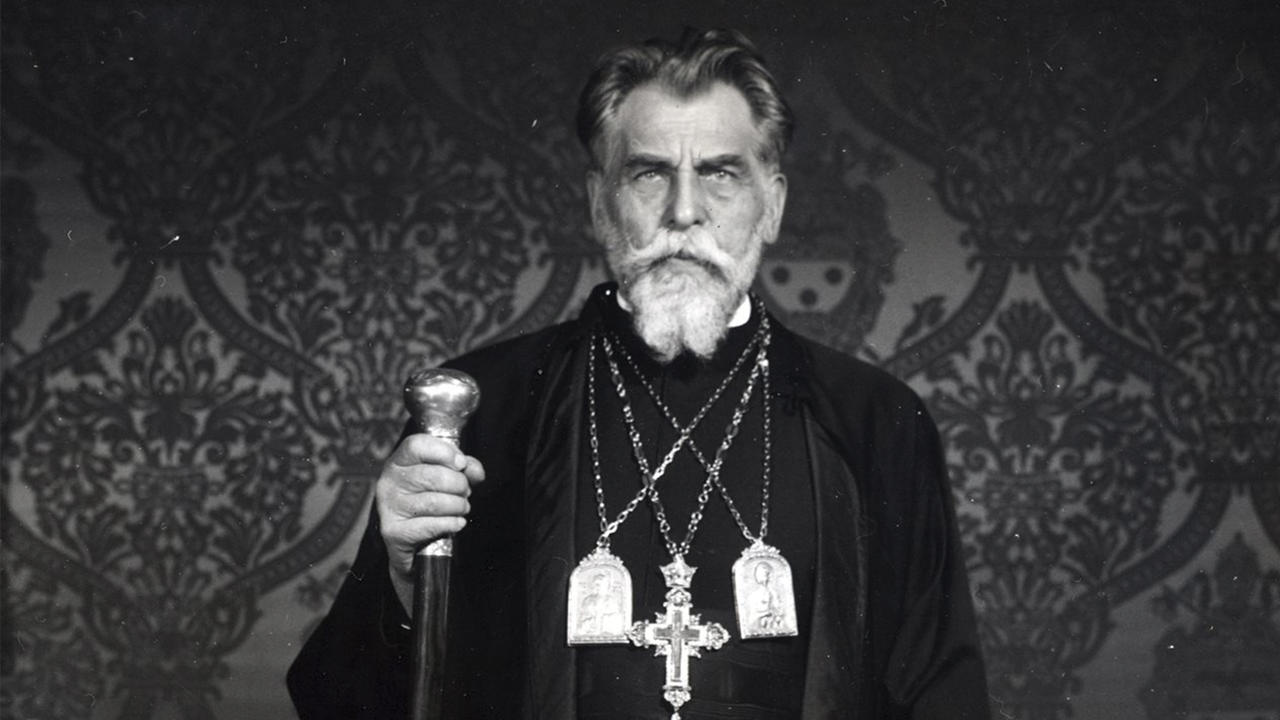

Josyf Slipyj (Ukrainian: Йосиф Сліпий) (17 February 1893 – 7 September 1984) was a Major Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Churchand a Cardinal of the Catholic Church. «Memoirs» of Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj is an important document of the denominational history of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, and it is also a valuable source for everyone who is interested in the history of religion in the USSR, Ukraine, Orthodox-Catholic and church-state relations. The author calls himself «the silent witness of the silent Church» («The silent witness of the silent Church» p. 427). In this declaration one feels the inexplicable tragedy of the personal destiny of Metropolitan and the destiny of his church. When one wanted to shout to the whole world about the crimes of the Soviet regime against the Church, they had to remain silent and all they could do was just pray. The persecuted church could not tell the world what was happening, its voice did not make it through the «Iron Curtain.» However, it survived and lived — in the catacombs and prisons, in the hearts of the common believers and in the confession of the martyrs.

Josyf Slipyj recorded his memoirs almost immediately after arriving in Rome but kept them private. His cautious silence about the persecution of Christians in the USSR was part of the arrangements for his release. And also that was a way for him to show pastoral care for those whom his revelations could hurt. And only today we can hear his voice – not as a candid narrative but as a document of the epoch which is full of silence and gaps. And these gaps tell more than the filled out pages. This is the case when you need to read between the lines. Metropolitan could not but write the memoirs – they were expected and clamoured for by both his church and all the free world. And the way he wrote them speaks of the difficult situation he and his church were in. Metropolitan had long before realized that the Soviet government had come to stay and one would have to negotiate with it. Therefore, he asked the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) to stop the armed struggle with the Red Army, «which had defeated Hitler himself, and so, in the course of time, would overcome the UPA too» (p. 479). That was why he stressed his civil allegiance to the Soviet state. It was for this reason that he did not write anything that could permanently destroy his relationship with the authorities and thus deprive the UGCC of the chance to be recognized in the USSR and the imprisoned priests to be released.

Obviously, the main concerns described by Metropolitan in the period were connected to the consequences of the Pseudo-Synod of 1946 when the UGCC was in fact dissolved. But he does not say much about it, and only criticizes Kostelnyk and the Orthodoxy. He writes a lot about the difficulties of the everyday life but in quite a monotonous way. He is also monotonous in describing people. He saw an informer or villain, mean or weak almost in everyone. It is noteworthy that there are practically no biblical quotations in the text. In general, «Memoirs» make an impression of a somewhat artificial, haphazard and unripe text. It seems that Norman Cousens was right when he wrote that even being in Rome, it was difficult for Josyf Slipyj to realize the reality of his freedom (p. 559). He wrote that in a way as if he were still in the USSR where one had to pay with their own blood and make the Church suffer for every free word.

It is known that Khrushchev, when he was negotiating the release of Metropolitan, was most afraid that the newspapers would publish articles «The Bishop Tells About the Bolsheviks Tortures» (pp. 537, 554). And Metropolitan was afraid of it as much. The nature of this fear was religious political. Obviously, he was afraid, not of terrorist attacks or new arrests, nor of the anti-religious campaign in the USSR stepping up; rather, he was worried that the unique chance of the Thaw period to legalize the UGCC under the pressure of anti-Stalin exposures and the existing unique international situation would be missed. Apparently, he shared the hopes of many for the «triumvirate» (the USA, the USSR and the Vatican) to be successful in the struggle for peace; and he reckoned that the church could get its tribute for the diplomatic mediation.

Apart from the «Memoirs», other accompanying documents are also collected under its cover. We see a different Josyf Slipyj in them: a diplomat, a historian, a polemicist and a pastor. In the documents on negotiations with the Soviet authorities, Metropolitan speaks the language of compromise offering his assistance in establishing relations between the USSR, the USA and the Vatican (p. 401) and asserting that the UGCC is quite compatible with the communist course (p. 397). In memoranda addressed to the See of Rome there is no politics anymore and there is nothing personal; there is nothing except for the caring for the Church and those devotees who represent it, heroes of faith and good priests (pp. 486-487). On the whole, the collection of texts helps to discover the image of Josyf Slipyj as a patriarch of the catacomb church. The author describes his 18 years of humiliation as just a background which he uses to constantly speak about the church. His personal history is completely subordinated to the main theme – the history of the UGCC. However, when you read some extracts, it seems that Metropolitan was so focused and concerned about his church that it prevented him from seeing other denominations as part of the unitary church. Describing the «camp of believers» (p. 220) that brought together Catholics, Orthodox, Protestants and various “sectarians,” he shows no interest in the possibilities of «camp ecumenism»; he speaks exceptionally illabout the Orthodox and he turns down every offer of the belivers from other denominations to have fellowship and do ministry together. Thus, because of fear of informers and agent provocateurs, believers would often deprive themselves of Christian fellowship and brotherly support. The texts convey the atmosphere of state terror against believers, general suspiciousness, fatality and self-censorship quite well.

Besides the value of the documents themselves, what also needs to be noted is the achivement of the editors of the publication. Fr. Dr. Ivan Dats’ko undertook a huge work on collecing different texts and structuring them. It is obvious that for him, who formerly served as a private secretary of Metropolitan, the arranging of the book was not only a professional challenge but also a spiritual duty. Dr. Maryia Horyacha’s contribution was equally as important. She checked, commented on the texts and edited them. The book leaves a strong impression: compiling editors and their work were devoted not so much to Metropolitan the martyr as to the church for which he had suffered; therefore, the published text is not so much a monument of history, as it is a gift, a lesson and a covenant for present and future generations of the universal Church of Christ.